How I empowered students to be advocates and 21st-century communicatorsAs a Spanish teacher in Title I public schools in Washington, D.C. and Vista, California, I served students who faced obstacles in life as a result of socio-economic status, race, sexuality, gender, origin, language background, and ability level. Systems of inequality and oppression surrounded my students so that their success was an uphill battle for which they were unprepared. My schools leveraged extracurricular programs to help students become self-advocates and leaders through after-school programs, learning extension, arts integration, and community partnerships. However, I wondered how I impacted students through teaching and learning: As their Spanish teacher, how did I provide access to learning opportunities that promoted self-advocacy and civic engagement? How did I help my students become successful global citizens and respectful communicators? The world language classroom has historically been focused on instruction of grammar and vocabulary with culture thrown in as an afterthought. Research on second-language acquisition has consistently indicated that teacher-oriented, grammar-based instruction does not help students develop communicative competence—the ability to communicate proficiently in all modes of communication with cultural sensitivity and global awareness. Have you noticed that many, if not most, students graduate high school or college without the ability to communicate effectively in the language they studied?

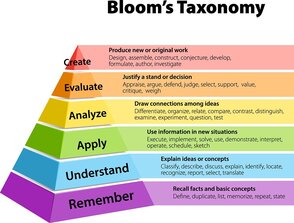

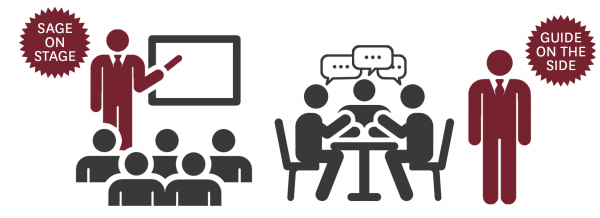

What are the implications?To learn more about these transformational teaching strategies, take a look at Dr. Noam Chomsky's Communicative Approach or Dr. Stephen Krashen's Theory of Second Language Acquisition. While the research on the benefit of communicative and input-based language instruction has been available for decades, many teachers still adhere to antiquated practices which have proven ineffective. In fact, some researchers and current teachers argue that there is no place for teacher-oriented, grammar-based instruction in the 21st-century world-language classroom. Armed with this knowledge, I knew that my classroom needed to be a safe and inviting learning environment in which students were the explorers, scientists, and architects of language use. My work was to guide learning as a facilitator, cheerleader, coach, and model of language learning (not even a model of language use). I did the work in my planning and collaboration with colleagues to transform the classroom into a microcosm of society in which students learned to successfully navigate complex and often challenging interactions they would face in the real world, using the target language as a means of self-expression and interlocution. Rather than taking notes from lectures or completing grammar practice, students in my classes engaged in learning activities that were immersive and comprehensible, promoting natural development of language competency. These activities included free reading, collaborative analysis of authentic texts, dramatic performance, project-based learning, artistic expression, research, etc. My role evolved from the "sage on the stage" to the "guide on the side" in a student-led classroom. (The image below does a wonderful job illustrating this, with the exception of the tie. Replace the tie with a scarf, and that was me!)  In his book Pedagogy of the Oppressed, Paulo Freire described the necessary changes in education in order to promote a student-driven classroom experience that empowers students to become fully integrated members of society. The role of teachers is not to regulate the way the world enters the students, but rather to help regulate the way the students enter the world (Freire, 1970, p.76). Teachers are not depositors of knowledge and information into students’ minds, but rather are the coaches and facilitators of students’ meaningful engagement with society. When I read this, it changed my thinking about what rigor looked like in my classes. By integrating Bloom’s higher-order thinking taxonomy in the use of the target language as a tool and means to engage in application, analysis, evaluation, and creation; I began to prepare students to become contributing members of society (Armstrong). My goal was to help students question the world they lived in, identify ways to improve it, and have a lasting positive effect on their communities and society. Zeke Cohen, the Executive Direction of the Baltimore Intersection—an organization which worked with students to become emboldened leaders and activists in inner-city communities and sought to demolish discrimination students based on race, ethnicity, and socio-economic status— explained that, “Power is about the ability to act, and to do for yourself and others. Our kids have the power in them. It’s not about us giving it to them; it’s about them finding it within themselves.” This idea of student empowerment was the driving force of Spanish-language instruction in my classrooms as I aimed to help students use Spanish to improve their communities and the larger society. I developed lessons and sought resources that increased students’ exposure to, and interaction with, language as it is used in the real world. I helped them find and their voice to think critically, interact responsibly, and express themselves effectively. That was the core of access and advocacy in the world-language classroom which moved my Spanish class from a place of irrelevance to importance in the lives of my students.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Currently ReadingAs I work toward developing the perseverance and drive to achieve my goals, I am reading Grit by Angela Duckworth. My biggest learning so far has been the importance of identifying and defining my inner compass, "...the thing that takes you some time to build, tinnier with, and finally get right, and then that guides you on your long and winding road to where, ultimately, you want to be" (p. 60). I use this compass to set goals, plan my daily actions, and reflect. Archives

October 2020

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed